Imperial Period

In the mid of the 1st century BC Corduba fell into the hands of Caesar and his army. They did not forgive the partisanship of the city to the Pompeian side, so they destroyed it and executed twenty thousand of its inhabitants. After years of recession, the battered city would be refunded (it has been traditionally thought that by Augustus himself, although there is no unanimity about it) with the status of colony. This brought the full Roman citizenship to its inhabitants, and a new patronymic that would be maintained only some centuries: Patricia. As the capital of Baetica, the most prosperous province of the West, the city expanded its urban area towards the south, to the very edge of the Baetis. For achieving this, the southern front of the republican wall was dismantled, increasing the intramural space to about 78 hectares. This new fence would have several doors, some of them monumental, such as the one located under the later Gate of Gallegos, in the western front, or the one that opened directly to the bridge.

From this moment, the new Colonia Patricia began an intense program of urban monumentalization following models imported from Rome. This can be seen in the construction of large buildings and the systematic use of noble materials such as marble; the reorganization of the road network and the provision of better services and infrastructures, including an efficient system of sewage disposal under streets paved with puddingstone; or the enlargement of the cardo maximus. This was a great avenue that crossed the town from north to south, which was twenty meters wide adding the width of the driveway and the side porches. Similarly, the former Republican Forum was paved with gray limestone slabs and surrounded by porticos and important civil or administrative buildings, such as the basilica, the curia or tabularium. There are no direct archaeological evidences of them, although the finding of various architectural and sculptural elements, oversized, confirm their presence, also related to the transcendental functions that the capital of the new province Baetica must have developed.

In the second decade of our era, the Forum adiectum or Novum was built immediately south of the former. This new complex was chaired by an octastyle colossal temple (only the capitals measure 1.60 meters in height) that followed the model of the Mars Ultor in Rome. It was preceded by an altar, similar to the Augustan Ara Pacis altar, surrounded by porticos built with high quality marble from different parts of the Empire. Imitating the Forum of Augustus in Rome, its exedras were presided by colossal sculptures of Aeneas fleeing Troy with his father and his son, and Romulo with the spolia opima. The porticos were a gallery of the illustrious sons of the city (summi viri). All this responds to the growing civil, administrative and religious needs of the new capital role of the city. In addition, this scenario exposed its strong and explicit adherence to the Urbs and the imperial dynasty.

The strong relationship between Colonia Patricia and Augustus is also reflected in the great monumental complex that was part of the Temple located in Claudio Marcelo street, somehow inspired in the Apollo Palatino in Rome. Hexastyle and pseudoperipteral, it was located in the center of a rectangular square with triple portico built over the old wall. As a clear symbol of the Pax Augusta, it acted as a colossal scenery that was, indeed, the eastern facade of the city, where the Via Augusta entered flanked by the circus of the colony. The typology of the complex allows ascribing to it functions of representation and honors related to the cult of the Emperor, perhaps initially Claudio. Its construction could have started under the auspices of Nero (41-54 AD) and could have been completed by Domitian (81-96 AD).

A third area of public worship could have existed in the area of Altos de Santa Ana, in whose surroundings there have been documented pedestals of statues and portraits of some members of the imperial family, particularly Julio-Claudian. Several sources point to the location here of a temple under the invocation of Diana, surrounded by a portico, and a possible macellum or market.

Huge buildings, capable of accommodating a large number of spectators, were built to host public performances (ludi). They strongly marked the urban topography. The theater, dedicated to the performance of various religious and civil ceremonies, was partially built following the Greek scheme and taking advantage of the natural slope of the plateau where the Republican Corduba was located, on its southeast side. This way, it was formed a complex of stepped terraces, a scenery with a Hellenistic touch, in whose funding took part some of the most illustrious and powerful families in the city, in an active evergetic exercise. With a diameter of 124 meters, it was the largest theater in Hispania, reaching a size very close to the Theatre of Marcellus in Rome and following its same constructive model. The preserved remains of the cavea or terraces are located under the current Archaeological Museum, while the orchestra would be fossilized in the present Jeronimo Paez square. The stage or scaena probably remained south of this latter. The building had an external monumental facade organized in three superimposed architectural orders (Doric-Tuscan, Ionic and Corinthian), supported by small pilasters. It probably collapsed after the earthquake that took place in the mid 3rd century.

The circus held horse and chariot races, activities usually related to the emperor worship. The remains of this building have been excavated in the garden of the Palace of Orive and correspond to the retaining walls of the northern stands. Its construction may have begun in mid 1st century. C, and was only in use until the end of the 2nd century, when it was abandoned for reasons still unknown. It is possible that it was replaced by a second circus, because there is an inscription that tells us about circus games sponsored by L. Iunius Paulinus in the early 3rd century.

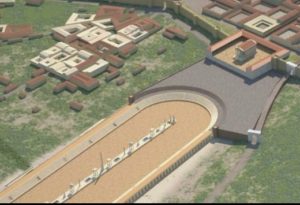

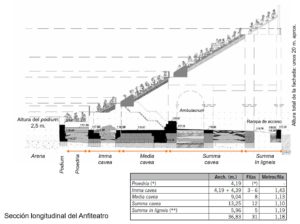

Also outside the walls, but on the western side of the city, the amphitheater was built. It was a building of elliptical plant in which the “games of blood” took place, such as gladiator fights and wild animal hunts or venationes, as well as public executions. This large building of solid plant and about 20 meters high is located just 200 meters away from the walled city. Its construction involved a complete remodeling of the suburb, including the road to Hispalis. The remains that have been documented in the grounds of the former Veterinary College (now the Rector’s office) belong to a whole section of the stands from the podium (or wall that delimited the arena) to the façade line. Other structures excavated in a nearby solar join this line, which has allowed a provisional calculation of the building’s major axis. It could have had about 178 meters length, which would turn it into one of the biggest on the empire. Built in the mid 1st century, it was in use until the late 3rd or early 4th century, when its materials started to be plundered. Thanks to the gladiatorial epitaphs recovered nearby, it is believed that Cordoba had a ludus gladiatorius hispanus, a gladiator school that could have provided fighters for all the Empire.

In the private field, the peristyle house or domus will be the most popular in Corduba from the late 1st century BC. Numerous examples of these houses have been documented, with arcaded courtyards, as the one located down the current Hotel Hospes del Bailío. The population growth and the existence of long periods of peace favored the progressive extension of the habitat outside the walls, usually in neighborhoods or vici organized along major roads, and not far from the spectacle buildings located outside the walls as well. Thus, we have examples such as the one located near the Amphitheatre, to the west, or the one under the current Plaza de la Corredera, to the east. There have been documented conspicuous examples of suburban domus in both of them, decorated with well known mosaics, such as those now displayed the namesake room in the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos. These vici will progressively disappear throughout the 3rd century. Finally, in the daily life of Colonia Patricia’s citizens, baths were very important. About them, some relevant archaeological evidence is preserved, as the baths exhumed in Concepción Street, very close to the northwestern gate of the Roman city (current Puerta Gallegos). However, until now there is no overall study about this topic.

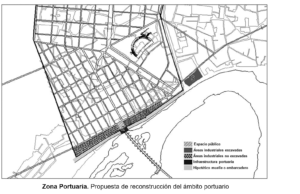

In the idiosyncrasy of Colonia Patricia and its inhabitants, the Baetis River, navigable for shallow draft boats until the very gates of the city, was fundamental. It was the main route out of goods and people to Rome, and provided the city with an important trade flow, both exporter and importer, which had among its main products oil, wine and cereals. The nerve center of this activity would be the port, which was made up of two essential infrastructures: the port complex, in the area of the current Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos, and a commercial complex within the walls, next to the Puerta del Puente. This space concentrated warehouses, shopping areas and manufacturing places distributed on both sides of the bridge, and even temples or shrines dedicated to oriental divinities.

Necropolis stood out outside the walls. They were real “cities of the dead” in which those who could afford it provided the maximum monumentality to their graves, of wide typology and strong Italic marks. Among them, for example, they can be distinguished the two large circular mounds, with 12 meters in diameter, located in front of Puerta de Gallegos and flanking the start of the via Corduba-Hispalis. Since the beginning, the rites of cremation and burial coexisted, although the first one was more popular during the Early Empire. The second was progressively imposed from the end of the 2nd century.

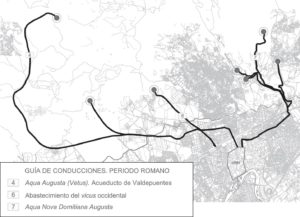

Finally, Colonia Patricia also had a large network of aqueducts, which provided with water public facilities, residential areas, commercial and leisure spaces, funerary gardens, etcetera. The first one, called Aqua Augusta in epigraphic sources (later on, Aqua Vetus), was built at the beginning of the early imperial time. For its erection, ingenious and very effective transport and control systems were used, such as inverted siphons or arcuationes. In times of Domitian, it was built the Aqua Nova Domitiana Augusta, whose remains have been located northeast of the city, along the Pedroche stream. At the end of the 1st century, a third aqueduct started to supply the Amphitheatre and the new western vicus. Some literary texts call it the Fontis Aureae Aquaeductus. Its remains can be seen today in the current bus station.

Bibliography

BAENA ALCÁNTARA, Mª D.; MÁRQUEZ MORENO, C.; VAQUERIZO GIL, D. (Comisar.) (2011): Córdoba, reflejo de Roma. Catálogo de la exposición, Córdoba.

CÁNOVAS UBERA, A. (2010): “La arquitectura doméstica de la zona occidental de Colonia Patricia Corduba” en VAQUERIZO, D. y MURILLO, J.F. (Eds.): El Anfiteatro Romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano. Análisis Arqueológico (ss. I-XIII d.C.), Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa, 19, vol. II, Córdoba, 415-439.

CARRILLO DÍAZ-PINES, J. R. (1999): “Evolución de la arquitectura doméstica en Colonia Patricia Corduba” en Córdoba en la Historia: La Construcción de la Urbe, Córdoba, pp. 75-86.

GARRIGUET MATA, J. A. (2002): El culto imperial en la Córdoba romana: una aproximación arqueológica, Córdoba.

GARRIGUET MATA, J. A. (2007): “La decoración escultórica del templo romano de las calles Claudio Marcelo-Capitulares y su entorno (Córdoba). Revisión y novedades”, en T. NOGALES, J. GONZÁLEZ (Ed.), Culto imperial: política y poder (Mérida, 2006), Roma, pp. 299-321.

JIMÉNEZ SALVADOR, J. L. (2004): “El templo romano de Córdoba”, en J. Blánquez, M. Pérez (Eds.), Antonio García y Bellido y su legado a la Arqueología Española (1903-1972), Serie Varia 5, Madrid, pp. 159-171.

LEÓN PASTOR, E. (2009-2010): “Portus Cordubensis”, Anejos de Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 2, Córdoba, pp. 45-72.

LEÓN MUÑOZ, A.; LEÓN PASTOR, E.; MURILLO REDONDO, J. F. (2008): “El Guadalquivir y las fortificaciones urbanas de Córdoba”, Las fortificaciones y el mar, Alcalá de Guadaira, pp. 261-290.

MÁRQUEZ MORENO, C. (2005): “Córdoba Romana: dos décadas de investigación arqueológica”, Mainake, 27, pp. 33-60.

MONTERROSO CHECA, A. (2011): “Córdoba romana. Historiografía abierta sobre arquitectura y urbanismo”, Antiquitas, 23, pp. 149-175.

MURILLO REDONDO, J. F. et alii (2003), “El templo de la C/ Claudio Marcelo (Córdoba). Aproximación al foro provincial de la Bética”, Romula 2, Sevilla, pp. 53-88.

MURILLO REDONDO, J.F. et alii (2010a): “El área suburbana occidental de Córdoba a través de las excavaciones en el anfiteatro” en D. VAQUERIZO y J.F., MURILLO (Eds.), El Anfiteatro Romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano. Análisis Arqueológico (ss. I-XIII d.C.), MgAC, nº 19, vol. I, 99-310.

MURILLO REDONDO, J. F. (2010b): “Colonia Patricia Corduba hasta la dinastía flavia. Imagen urbana de una capital provincial”, en GONZÁLEZ VILLAESCUSA, R. (coord.): Simulacra Romae II: Rome, les capitales de province (capita provinciarum) et la création d’un espace commun européen: une approce archéologique, pp. 71-94.

MURILLO REDONDO, J. F. (2011): “El anfiteatro cordubense”, en Córdoba reflejo de Roma. Córdoba. pp. 236-239.

PORTILLO GÓMEZ, A. (e.p.): “La policromía del templo de la calle Morería en el forum novum de Colonia Patricia”, en Archivo Español de Arqueología, nº 88, 217-232.

PORTILLO GÓMEZ, A. (e.p.): “La decoración arquitectónica del templo de la calle Morería en el forum novum de Colonia Patricia”, en Thiasos, Vol. 4, Roma.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D. y MURILLO, J. F. (2010): “Ciudad y suburbia en Corduba. Una visión diacrónica (siglos II a.C. – VII d.C.)”, en VAQUERIZO GIL, D. (Ed.), Las áreas suburbanas en la ciudad histórica. Topografía, usos, función. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa 18, Córdoba, pp. 455-522.

PIZARRO BERENJENA, G. (2013): El abastecimiento de agua a Córdoba. Arqueología e historia. Universidad de Córdoba. Servicio de Publicaciones. Córdoba.

RODRÍGUEZ NEILA, J. F. (2010): “Corduba romana, capital de la provincia Hispania Ulterior Baetica”, en ESCOBAR CAMACHO J. M.; LÓPEZ ONTIVEROS, A.; RODRÍGUEZ NEILA, J. F. (Coords.), La ciudad de Córdoba: origen, consolidación e imagen, Córdoba, pp. 23-82.

RUIZ OSUNA, A. B. (2009): Topografía y monumentalización funeraria en Baetica: conventus Cordubensis y Astigitanus. Universidad de Córdoba.

RUIZ OSUNA, A. B. (2010): Colonia patricia, centro difusor de modelos: Topografía y monumentalización funerarias en Baetica, Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa 17, Córdoba.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D. (2001): Funus Cordubensium. Costumbres funerarias de la Córdoba romana, Córdoba.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D. (Ed.) (2002a): Espacio y usos funerarios en el Occidente romano, Córdoba, 2 vols.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D. (dir.) (2003): Guía Arqueológica de Córdoba, Córdoba.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D. (2010): Necrópolis urbanas en Baetica, Documenta 15, ICAC y Universidad de Sevilla.

VAQUERIZO, D., MURILLO, J. F. (eds.) (2010a): El anfiteatro romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano. Análisis Arqueológico (ss. I-XII d.C.). Córdoba.

VAQUERIZO, D.; MURILLO, J. F. (2010b): “Ciudad y suburbia en Corduba. Una visión diacrónica (siglos II a.C.-VII d.C.)”, en D. VAQUERIZO (ed.), Las áreas suburbanas en la ciudad histórica. Topografía, usos y función. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa 18, Córdoba, pp. 455-522.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D., RUIZ OSUNA, A. (2010): “In amphitheatro. Munera et funus”. Análisis arqueológico del anfiteatro romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano (ss. I-XIII d.C.). Quarhis: Quaderns d’Arqueologia i Història de la Ciutat de Barcelona, Nº. 6, pp. 204-206.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D.; MURILLO REDONDO, J. F.; GARRIGUET MATA, J.A. (2011): “Novedades de arqueología en Corduba, Colonia Patricia”, en J. GONZÁLEZ y J.C. SAQUETE (eds.), Colonias de César y Augusto en la Andalucía romana, Roma, pp. 9-45.

VAQUERIZO GIL, D. y RUIZ BUENO, M. D. (2015): “Últimas investigaciones arqueológicas en Corduba, Colonia Patricia, una propuesta de síntesis”, en MARTÍN BUENO, M.; SÁENZ PRECIADO, C. (coords.): Modelos edilicios y prototipos en la monumentalización de las ciudades de Hispania. Zaragoza, pp. 15-32.

VENTURA VILLANUEVA, A.; PIZARRO BERENGENA, G. (2010): “El Aqua Augusta (acueducto de Valdepuentes) y el abastecimiento de agua a Colonia Patricia Corduba, investigaciones recientes (2000-2010)”, Las técnicas y las construcciones en la ingeniería romana, pp. 175-204.