Low Roman Empire

The transition from the classical Colonia Patricia to the Corduba late ancient was a long-lasting process that had its roots at the end of the second century (abandonment of the circus), but which received a definite push from the middle of the third century onwards.

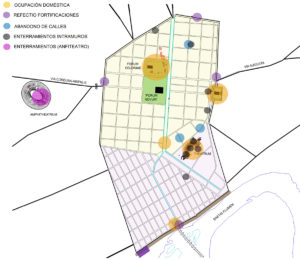

The Low Roman Empire was a key period in the history of Cordova, as a new urbanism gradually took shape that acquired its definitive features in the sixth and seventh centuries. Among the most characteristic features, we can point out the gradual withdrawal of the population into the intramural space, as between the second quarter of the third century and the first decades of the fourth century, the suburban neighborhoods surrounding the city (vici) were progressively abandoned. This withdrawal did not imply a densification of the intramural surface, where the general trend was the appearance of a less cohesive urbanism in which three types of lots were alternated, including those occupied with different publics; those less densely occupied, and others event emptied. In parallel, the southern area of the city (closest to the river, the bridge and the port) acquired progressive weight and importance, which explains the installation at this point of the center of civil power (civil complex) and religious (complex Episcopal) of the city.

The progressive importance of the southwestern section of the city explains the continuous reinforcement of the wall perimeter through this area. Although the entire walled enclosure was continuously repaired throughout the Low Roman Empire, the most relevant works took place in the space presumably occupied by the original port complex, where in the 5th century a primitive civil, with a fortified complex (castellum) was erected.

The continuous maintenance of the wall perimeter contrasts with the evolution of the road and hydraulic infrastructure. In the case of the streets and sewers, these already suffered some changes during the Severian period that intensified between the second half of the third century and the fourth and fifth centuries. Within this time frame, it has been detected not only a relaxation in the maintenance of certain roads and sewers (i.e. the partial or total invasion of certain streets, the filling of some sewers, and the covering of the primitive stone pavements of some streets), but also the continuous maintenance of other streets of the city.

The gradual decrease in the maintenance of the sewerage system of Cordova was cause by several factors. In the intramural space a decisive factor was the abandonment of the two aqueducts (Aqua Augusta Vetus and Aqua Nova Domitiana Augusta) that supplied this sector. As a result, only those sewers whose inclination or internal light allowed their natural cleaning, continued in use. The progressive abandonment of the aqueducts led to the disappearance of public and private fountains, so the bulk of the population had to use to other alternative supply systems, such as wells and cisterns.

The partial disuse of Aqua Augusta Vetus in the 50s and 60s has been linked to an earthquake that could also caused the partial destruction of the theater. Corduba‘s public and semi-public architecture underwent major transformations in the second half of the third century and the first decades of the fourth century. In this period, the city lost much of its most monumental facilities (theater, amphitheater, forum novum, the upper terrace of the religious complex of Claudio Marcelo’s street). These dynamics did not affected other constructions such as the colonial forum (in use until the 50s and 60s of the fourth century), two mercantile complexes located in the southern facade of the city, and mainly, several thermal establishments which remained in use until the beginning of the fifth century.

However, the main novelty of this period was the construction of the impressive suburban complex of Cercadilla. Raised towards the end of the third century-early fourth, its exact functionality remains the subject of debate. In spite of this, at the moment it is quite extended the possibility that in the first moment, or shortly after its erection, it was the seat of the vicarius hispaniarum, that is to say, of the maximum representative of the entity known like diocesis hispaniarum. Subsequently, towards the second quarter of the fourth century, the whole complex was likely to be under the control of the Church.

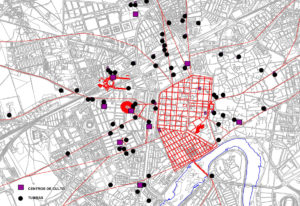

In connection with Christian architecture, after the legalization of Christianity thanks to the Edict of Milan (313), a phase of monumentalization began, which throughout the Empire meant the construction of both the cathedral church and different suburban funeral churches. Although Cordova should have taken part in these dynamics, we have scarce archaeological information about this architecture. In the intramural space, it is most likely that by the fourth and fifth centuries, a first Episcopal Complex was erected in the space occupied today by the present Mosque-Cathedral. Outside of the walled enclosure, several martyrdom centers must have been set up dedicated to the local martyrs, but their archaeological detection remains problematic.

Faced with Christian religious architecture, in Cordova we have more data about domestic structures. In the intramural space we have evidences of several dynamics that include the reform of several properties (new mosaics, installation of fountains, ponds or deposits); the abandonment of certain pre-existing residential properties, and the construction of new houses (modest or of a certain entity) on old monumental complexes already abandoned. Outside the wall, the most significant trends are the abandonment of suburban vici, and especially, the construction and monumentalization of all types of residential properties scattered throughout the suburban and peri-urban space.

In relation to artisan and productive activities, one of the consequences derived from the abandonment of the old monumental complexes, was its reconversion into the new urban quarries. From these old buildings thousands of cubic meters of stone and marble blocks were extracted, although their exact destination remains unknown. Another important novelty was the proliferation of artisan areas throughout the intramural space.

The multiplication of these productive centers (dedicated to the work of bone, marble, metal, etc.) was contemporaneous with the appearance in the intramural space of both landfills of various kinds, as well as burials. In the case of the funerary world, the third century was characterized by an increasing mobility and decentralization of suburban cemetery areas. From the third century there is evidence of trends such as the continuity of certain pre-existing necropolis, the abandonment of others, and the appearance of new funerary sectors at points characterized by their heterogeneous previous function (domestic, artisanal, agricultural, etc.). We should also take into consideration the impact of the Christian religion, which in Cordova had its material reflection on a rich and varied collection of sarcophagus that reflect the progressive Christianization of the local aristocracy.

Bibliography

ALORS, R.M. et alii (2015): “La Córdoba del siglo de Osio: una ciudad en transición”, en A.J. REYES (ed.), El siglo de Osio de Córdoba, Madrid, 55-99.

AA.VV. (2008): Atlas cronológico de la historia de España, Madrid.

CARRILLO, J.R. et alii (1999): “Córdoba de los orígenes a la Antigüedad Tardía”, en F.R. GARCÍA, y F. ACOSTA (coords.), Córdoba en la historia: la construcción de la urbe, Córdoba, 37-74.

HIDALGO, R. (2005): “Algunas cuestiones sobre la Corduba de la antigüedad tardía”, en J.Mª. GURT y A.V. RIBERA (coords.), VI Reunió d´Arqueologia Cristiana Hispànica, Barcelona, 401-414.

JURADO, S. (2008): “El centro de poder de Córdoba durante la Antigüedad Tardía: origen y evolución”, Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 19, 203-230.

MARFIL, P.F. (2000): “Córdoba de Teodosio a Abd al-Rahman III”, en L. CABALLERO y P. MATEOS (coords.), Visigodos y Omeyas. Un debate entre la Antigüedad Tardía y la Alta Edad Media. Anejos de Archivo Español de Arqueología, nº 23, Madrid, 117-141.

MURILLO, J.F. et alii (1997): “Córdoba: 300-1236 d.C., un milenio de transformaciones urbanas”, en G. DE BOE y F. VERHAEGHE (eds.), Urbanism in Medieval Europe. Papers of the “Medieval Europe Brugge 1997”, Conference, vol. 1, Zellik, 47-60.

MURILLO, J.F. et alii (2010): “El área suburbana occidental de Córdoba a través de las excavaciones en el anfiteatro. Una visión diacrónica”, en D. VAQUERIZO y J.F. MURILLO (eds.), El anfiteatro romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano. Análisis arqueológico (ss. I-XIII d.C.). Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 19 vol. I, Córdoba, 99-310.

PIZARRO, G. (2014): El abastecimiento de agua a Córdoba. Arqueología e Historia, Córdoba.

RODRÍGUEZ, J.F. (1988): Del amanecer visigodo al ocaso visigodo. Historia de Córdoba, nº 1, Córdoba.

RUIZ, M.D. (2016): Topografía, imagen y evolución urbanística de la Córdoba clásica a la tardoantigua (ss. II-VII d.C.). Tesis Doctoral (inédita), Córdoba.

SÁNCHEZ, I. Mª. (2010): Corduba durante la Antigüedad tardía. Las necrópolis urbanas. Bar International Series 2126, Oxford.

VAQUERIZO, D.; MURILLO, J.F. (eds.), (2010a): El anfiteatro romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano. Análisis arqueológico (ss. I-XIII d.C.). Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 19, vol. II, Córdoba.

VAQUERIZO, D.; MURILLO, J. F. (2010b): “Ciudad y suburbia en Corduba. Una visión diacrónica (siglos II a.C.-VII d.C.)”, en D. VAQUERIZO (ed.), Las áreas suburbanas en la ciudad histórica. Topografía, usos y función. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 18, Córdoba, 455-522.

VAQUERIZO, D.; GARRIGUET, J.A.; LEÓN, A. (eds.), (2006): Espacio y usos funerarios en la ciudad histórica, Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 17, Córdoba.

VAQUERIZO, D.; GARRIGUET, J.A.; LEÓN, A. (eds.), (2014): Ciudad y territorio: transformaciones materiales e ideológicas entre la época clásica y el Altomedievo. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa, nº 20, Córdoba.

VENTURA, A. et alii (eds.), (2002): El teatro romano de Córdoba. Catálogo de la exposición, Córdoba.